“Aye, fight! But not your neighbor. Fight rather all the things that cause you and your neighbor to fight.” ~ Mikhail Naimy

While the title of this article may trigger some persons to ask if I have Dangote cement or petrol in my pockets, if I can be given just some time to explain, maybe my integrity would be unquestioned. Yes, it is true that trailers either belonging to or affiliated to the Dangote Group have wreaked havoc on the Nigerian public, including the recent killing of Ruth Otabor, but while it is easy to request for Uncle Dangote’s head on a spike, the accidents are not of his making. Rather, they are simply a symptom of a more complex problem to be solved.

There is no data on the number of Dangote trailers involved in accidents, but the latest available Road Transport Data (Q2 2024) from the National Bureau of Statistics shows that 234 trailers were involved in accidents out of 3,612 (6.5%) accident vehicles in that quarter. Knowing that the vehicles affiliated to Dangote account for less than 20% of the total number of trailers on Nigerian roads, it would have been easy to pin the blame on Dangote if we had data to show that their trailers account for a disproportionate number of accidents. While this granular data does not exist, we could determine anecdotally from media reports that trailer accidents are not the exclusive preserve of Dangote trailers. If not, for 234 trailers nationwide in one quarter (90 days), we would have been hearing of a new accident involving a Dangote trailer at least once every day.

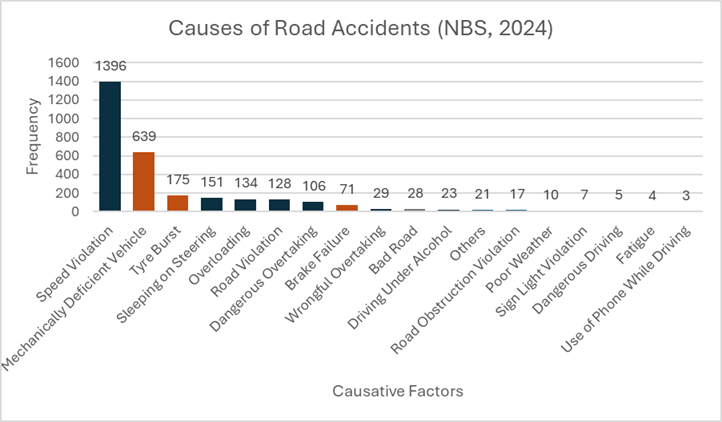

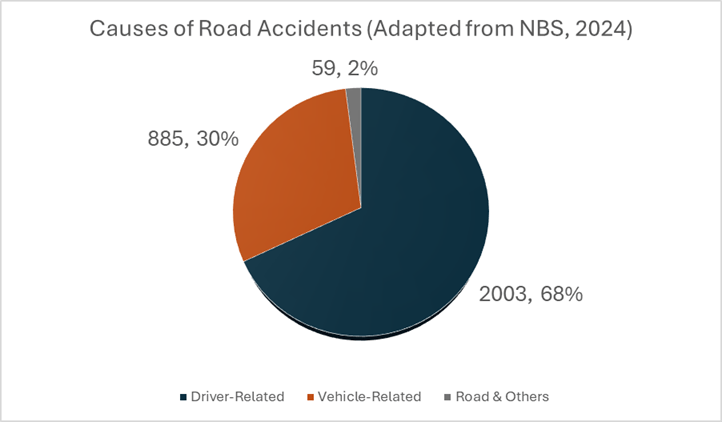

Moving on from trailer statistics, the graph above shows that 47% of accidents are due to speed violations, while 22% are due to mechanically deficient vehicles and 6% are due to burst tyres. This is where the real problem lies. We can attack the “monopophilic” Dangote all we want, but without addressing structural issues with driver qualifications and behaviour, vehicle roadworthiness, and road driveability, we would merely be punching at shadows.

Yes, it is true that a certain Dangote driver did not have a driver’s licence. But is this a Dangote problem or a government problem? How many drivers on Nigerian roads today do not have any licence to drive? Why are they on the roads despite the countless legal and illegal checkpoints set up by the police, Federal Road Safety Corps, VIO, agberos, etc. How many Nigerian drivers passed through a driving school? How many drivers can point to road signs and say what each sign means? If drivers have no understanding of road signs nor of their obligations as drivers, why do we expect them to observe speed limits? How are trailer drivers selected? We see young boys serve as “bus boys” (driver’s assistant) for a short while and get upgraded to driving trailers without any licensing. Who checks this? We see drivers smoking while driving or even clearly inebriated. Who checks this? Is it the police officers—some of whom have been seen drinking and smoking weed while on uniform?

Moving on to vehicle worthiness, how many vehicles on Nigerian roads are fit to be used on the roads? Unfortunately, while I would have loved to hammer on this point, I am held back by the practicalities around fit vehicles. Due to economic conditions, most vehicles on Nigerian roads are purchased as used vehicles. I understand that mandating a certain grade of vehicles would not work since most persons clearly cannot afford them and any forced attempt would spike inflation further, but at the very least, we can mandate good maintenance practices. A 30-year-old trailer can still serve well if subjected to proper maintenance by competent automobile mechanics.

As for road driveability, if we were true to ourselves, we would agree that a good number of accidents are caused by terrible roads. A loaded trailer, or any vehicle for that matter, should not be doing pothole dodging gymnastics. Each time a trailer has to assume a contorted shape to bypass a pothole, the trailer’s load distribution changes, with the centre of gravity moving to a point that could exceed stability limits and cause the trailer to lose balance. The driving gymnastics also contribute to a higher occurrence of burst tyres. Sometimes, accidents occur because a driver decides to violate traffic rules (like following a wrong route) to avoid a bad road. So, who is responsible for fixing the bad roads?

Of course, nothing in this article says the Dangote Group should not address internal issues within their control like improved driver selection and training, frequent quality checks, speed limiters, fleet monitoring, random drug and alcohol tests, enforced vehicle maintenance, etc. Taking a few percentage points from their profits to fund responsible behaviour would not kill their business. After all, nobody is taking any cash to the grave. Dangote can beat the normal distribution of accidents in Nigeria and show naysayers that he cares for the average life on the roads beyond wanting to increase his standing in the global billionaires’ list and despite the systemic issues in Nigeria.

But beyond Dangote’s shenanigans, Nigeria needs to have a hard discussion about enabling safer road transport. If we do not address the root causes driving wasteful loss of lives and assets on the roads, anything else would be cosmetic just like applying make-up on a face riddled with industrial-grade pimples. Let’s end with a quote from India’s Narendra Modi: “Good governance is not firefighting or crisis management. Instead of opting for ad-hoc solutions, the need of the hour is to tackle the root cause of the problems”.